Christopher Thiéry “L’enseignement de la prise de notes en interprétation consécutive: un faux problème” in DELISLE, Jean, réd., L’enseignement de l’interprétation et de la traduction : de la théorie à la pédagogie, Cahiers de traductologie no 4, Éditions de l’Université d’Ottawa, Canada, 1981, 296 p, pp. 99-112.

Résumé de lecture Danielle-Claude Bélanger, 1990

1. Définition de l’interprétation consécutive

Il existe une forme d’interprétariat spontané qu’on peut dire de liaison», c’est l’action d’une personne qui connaît les langues en présence dans un échange linguistique et qui aide les interlocuteurs à comprendre le message en leur résumant en substance les informations véhiculées. Le plus souvent elle parle à la troisième personne».

L’interprétation de conférence se distingue de l’interprétariat spontané. Dans l’interprétation en consécutive, une formation spéciale doit être suivie. L’interprète parle à la première personne» à la fin de l’intervention de l’orateur, ceci dans un cadre formel et structuré.

2. Les trois temps de l’interprétation consécutive

L’interprétation en consécutive consiste à écouter une information, à se l’approprier mentalement et à la rendre pour un auditoire donné. Évidemment, cela présuppose un maîtrise parfaite des langues utilisées. Nous pouvons distinguer trois temps particuliers dans l’exécution d’une interprétation en consécutive.

A. Sens du message de l’orateur

Dans ce premier temps fort, il s’agit d’enregistrer le message. Dans une situation habituelle de communication, orateur et auditoire partagent le même univers symbolique, les auditeurs capteront le message de façon naturelle. Cela n’est pas le cas pour l’interprète car le message ne lui est pas destiné et il devra fournir un effort conscient afin d’enregistrer l’information et comprendre le message.B. Discours de l’interprète

Une fois le premier temps écoulé, l’interprète devra rendre le message dans la langue du destinataire. Mais pour que son acte de parole soit réussi, il doit posséder quelques caractéristiques nécessaires à une bonne communication. C’est-à-dire que l’interprète doit posséder une volonté de dire en s’appropriant celle de l’orateur et une crédibilité lors de son exécution. Il doit posséder certains talents oratoires qui lui permettront de respecter l’intention première quant au fond, à la forme et à l’impact.C. Prise de notes

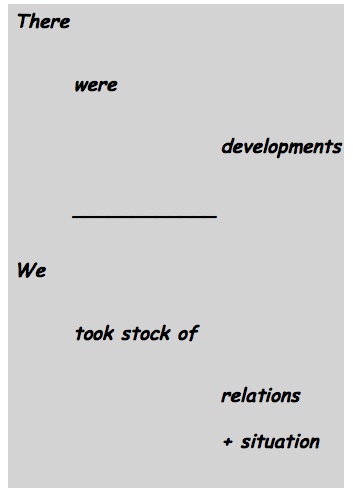

La prise de notes est généralement nécessaire à l’interprétation en consécutive. C’est cependant un outil accessoire que certaines personnes pourront choisir d’ignorer. Les notes rendront le sens du message, elles n’en feront pas le résumé. Elles ne seront pas non plus de style sténographique. Elles représentent vraiment un outil dont la personne interprète se servira à sa convenance. Aussi, nulles normes, ni en regard de la production de notes, ni en regard de leur consultation, ne pourront être relevées.

3. Enseignement de l’interprétation consécutive

Les recherches et les analyses dans le domaine de l’interprétation consécutive furent tardives et longtemps superficielles car la profession ayant pris naissance de façon spontanée après la seconde guerre ne fit sentir que tard aux interprètes professionnels l’importance de comprendre et d’analyser les processus mis en oeuvre dans leur travail. Les premiers modèles étaient mécaniques et portaient surtout sur la prise de notes, en fait ils étaient peu utilisés car chaque interprète développe son propre système dans un effort créatif pour s’approprier les messages. Cela appartient au style propre de chacun. Dans l’enseignement de l’interprétation, il faut encourager et accélérer l’acquisition de ce savoir-faire, on distinguera trois temps : le premier temps fort consiste à donner un sens au propos de l’orateur par une construction intellectuelle ; dans le deuxième temps fort, l’interprète crée son propre discours ; dans le temps faible (accessoire), l’interprète se crée une méthode originale et adaptée aux circonstances pour noter. On peut pratiquer tout cela en classe.

Premier temps fort : l’enregistrement du message

Étape difficile : il ne faut pas se concentrer sur la forme du message mais sur son sens. En classe, on pourra faire des exercices d’extraction de sens. Il faut s’appuyer sur la capacité des jeunes interprètes à retenir le sens de deux ou trois idées mais sans fixer leur attention sur la forme en mémorisant ou en notant. Il faut faire preuve d’une souplesse d’esprit dans l’écoute. Il faut se mobiliser totalement face à l’orateur, par exemple en jugeant ses idées. Cela améliore la rétention du message.

Deuxième temps fort : réexpression du message

Il faut distinguer chez l’étudiant ou l’étudiante les insuffisances linguistiques et les difficultés de rétention. Le plus important est la rigueur de l’expression de la pensée, quelles que soient les idées défendues. Puis vient l’entraînement en tant que tel à la performance oratoire. Le plus difficile consiste à s’identifier à l’orateur tout en assimilant par soi-même la matière exposée, car on ne peut interpréter correctement ce qu’on n’a pas compris.

Temps accessoire : prise de notes

On ne peut noter que ce qu’on a compris. Le professeur doit insister sur cela. Il n’y a pas de réponse générale à la question de savoir quoi noter, il ne peut donner que des conseils pratiques. Car les notes sont une mémoire externe.

Conseils pratiques

1. Donner la priorité à l’enregistrement ; 2. noter lisiblement ;

3. hiérarchiser les idées dans l’espace de la feuille ; 4. utiliser des symboles déjà connus ; 5. veiller à la qualité du papier et du crayon ; 6. numéroter les idées ; 7. biffer les passages restitués ; 8. les notes sont consultées avant chaque restitution du message et non pas lues.

4. Conclusion

L’erreur à éviter en interprétation consécutive consiste à faire passer les notes avant le sens, la forme avant le message. L’interprète qui se concentre sur ses notes est incapable de restituer le message parce qu’il ou elle est trop absorbé par la production des notes et pas assez par la compréhension du message. Il ne faut pas oublier que la prise de notes n’est qu’un temps accessoire.