“The first rule of consecutive interpreting is that the real work must already have been done when you start reading back your notes: the text, its meaning and the links within it, must have been perfectly understood.”

Jean-Francois Rozan

The beginning of note-taking?

This page describes two exercises that are very useful when you start learning to take notes. The exercises are designed to lead you towards structured notes, but will also require you to analyse the source speech properly. They will also promote memorisation (because of the better analysis you do).

What is an idea?

For the purposes of note-taking we’ll use Subject Verb Object as the basis of each idea. That is the smallest group that tells us Who Does What. It is also usually the smallest useful unit in language.

For more about different definitions of “idea” in interpreter training follow this link.

Exercise 1 – highlight SVO

This Stabilo advert shows us a great example of how to fish the most important elements – the Subject, Verb and Objet, out of a longer text.

Let’s go through the speech transcript below and see if we can find, and highlight, the SVO groups. (The text below is a speech given by Australian Minister David Little Proud in August 2020.)

Look, over 100 years ago our forefathers put on a map lines that formatted our states and since then, over that 100 years, regional and rural Australia has evolved past those – we become integrated in terms of agricultural production systems, in terms of our community, in terms of our healthcare. And what we’ve seen from COVID-19 is that some of the arbitrary restrictions being placed on regional and rural Australia by the states have had serious impacts on that integration.

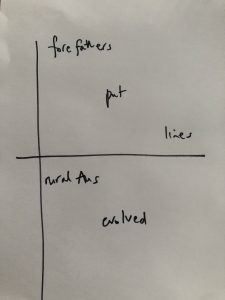

Exercise 2 – note SVO diagonally across the page

This second exercise is to go through the speech transcript and see if you can find, and then note on a separate sheet of paper, the SVO groups.

Look, over 100 years ago our forefathers put on a map lines that formatted our states and since then, over that 100 years, regional and rural Australia has evolved past those – we become integrated in terms of agricultural production systems, in terms of our community, in terms of our healthcare. And what we’ve seen from COVID-19 is that some of the arbitrary restrictions being placed on regional and rural Australia by the states have had serious impacts on that integration.

Forefathers… put… lines…

You’re probably thinking that if you made those notes you wouldn’t remember the rest of that longish sentence is. Interestingly when you choose what to note, and what not to note you remember far more of what you didn’t note down. Also remember this is just the beginning. As you learn more about note-taking, and about how your memory works, you can add more detail into your version of the speech.

The recall process might go something like this…. “Forefathers”, how long ago? 100 years… “put lines”, where? On a map? So? Lines on maps delineate countries, or here states. And so on

Rural Australia… evolved…

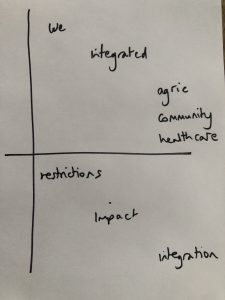

We… integrated… agriculture & community & healthcare…

Restrictions… impact… integration…

You’ll notice there are several objects in the second to last SVO group. See verticality for more on how to deal with that.

Have a look at what that might have looked like as a set of notes

Remember these notes are not the final product. This is very early stage note-taking and there are many improvements to come, eg. Abbreviations and symbols.

For more on the history of S-V-O in note-taking (who wrote what, when) see this article