Qu’est-ce que la langue ‘B’ ?

– Il faut d’abord préciser la nature, pour l’AIIC et les interprètes de conférence professionnels, de cette ‘langue B’. Il s’agit d’une langue active, capable d’être employée quant à moi en consécutive et en simultanée. Certains acceptent que la combinaison C > B peut ne pas être offerte, ou l’être seulement en consécutive, mais l’ avis personnel de l’auteur est qu’une langue active doit l’être à partir de toutes les autres langues de travail de l’interprète.

– En parlant ici de la langue ‘A’ dite ‘maternelle’, j’entends un niveau de langue hors du commun, car il ne suffit pas d’être ressortissant d’un pays et d’être d’une certaine expression linguistique pour prétendre maîtriser cette langue comme se le doit un interprète de conférence. Il s’en suit que certaines langues ‘B’ peuvent être supérieures, comme vecteurs d’expression, à une langue ‘A’ moyenne.

– N’oublions pas non plus que ‘biactif’ n’est pas synonyme de ‘bilingue’ ; les vrais bilingues (culturels, émotionnels, linguistiques..) sont très très rares, et ne sont pas forcément de bons interprètes du fait de leur seul bilinguisme. A titre d’exemple, sur le 39 interprètes permanents actuellement en exercice à l’OTAN, tous biactifs, 6 sont bilingues, soit ‘double A’ d’après les catégories AIIC.

– On rencontre aussi assez fréquemment le cas de figure de l’interprète en herbe qui ne possède pas de langue à proprement parler maternelle et qui, à la différence du bilinguisme auquel sa vie précédente a pu lui laisser croire, possède deux langues ‘B’, aucune n’étant maîtrisée au niveau requis chez l’interprète de conférence. En ce cas-ci, la carrière d’interprète de conférence n’est malheureusement pas une aspiration réaliste.

– Il est aussi possible de trouver des interprètes capables de travailler vers trois langues, mais il s’agit ici d’un phénomène des plus rares – je me méfie de la grande majorité des linguistes qui prétendent à de telles compétences, car elles sont le plus souvent synonymes d’une interprétation de qualité médiocre. Comme on le dit en anglais « Fools rush in where angels fear to tread ». Le vrai professionnel connaît ses limites…

– Il convient d’oublier ici toute notion de ‘retour dépannage’ tel qu’enseigné par les écoles belges, car celui-ci n’a pas lieu d’être, et dévalue à la fois l’interprète et sa profession. En clair, on doit pouvoir offrir une prestation professionnelle et de haute qualité, ou se taire…

– La langue ‘B’ telle que pratiquée au niveau le plus élevé en conférence (par exemple à l’OCDE, au Conseil de l’Europe, à l’OTAN, au sein des différents ministères nationaux..) est donc une deuxième langue dont la maîtrise se situe, grosso modo, à un niveau légèrement en-deçà de celui d’une langue maternelle d’interprète (entre disons 2% et 15%, il étant entendu que ce genre de mesure n’a que peu de sens). Cette langue se pratique à un très haut niveau de richesse et de souplesse, et qui dépasse sensiblement le niveau de langue du ressortissant lambda, même diplômé universitaire, du pays en question.

– En langue ‘B’ on peut accepter un léger accent étranger, du moment que celui-ci ne représente jamais une entrave à la compréhension. Un nombre très réduit d’erreurs (par exemple de genre dans les langues latines ou d’accent tonique en anglais) peut aussi être toléré, en fonction du contexte, car il ne s’agit pas ici d’une langue qui se prétend maternelle.

– Il est bien entendu impossible d’établir un pourcentage des langues ‘C’ que l’on peut envisager de convertir en langue ‘B’, mais il faut comprendre que, à la différence de la langue maternelle, une langue ‘B’ peut se fabriquer. En mon expérience de pédagogue de 18 ans, entre environ 15% et 20% des étudiants-interprètes pourraient à terme, une fois bien conseillés et bien guidés (et à force de travail acharné !), envisager le rajout d’une langue ‘B’ à leur combinaison.

Pourquoi vouloir se doter d’une deuxième langue active ?

Maintenant que nous savons plus ou moins ce qu’est une langue ‘B’, voyons un peu son utilité.

– Vous savez que, grosso modo, les interprètes de conférence professionnels se scindent en deux grandes catégories :

- * le profil dit « classique », où l’interprète possède une langue maternelle active, et un certain nombre de langues passives

- * le profil dit « biactif », où l’interprète possède deux langues actives et éventuellement un certain nombre de langues passives – Dans le monde d’aujourd’hui, où commerce et globalisation sont rois et se véhiculent par une version bâtarde et appauvrie de la langue anglaise, le temps est en permanence compté, les budgets serrés, et on se passera volontiers de l’interprétation là où c’est possible. Néanmoins, pour des raisons soit de technicité des rencontres, soit de nature davantage politique et de prestige, l’interprétation de conférence reste un métier prisé qui demeurera de mise là où une communication approfondie et subtile est nécessaire. – Le marché international desservi par les interprètes se scinde grosso modo en deux : le privé/commercial et l’étatique (gouvernements, organisations internationales..).

Dans certains cas de figure devenus rares, il reste souhaitable de conserver une kyrielle de langues de travail et de rechercher donc des interprètes qui en possèdent au moins trois de manière passive ; on pense notamment ici, bien entendu, à l’Union Européenne et, dans une moindre mesure, à l’ONU.

Pour l’ensemble des autres secteurs où les hommes et les femmes sont appelés à dialoguer, le souci de la communication va de pair avec celui de la rentabilité, de la vitesse et de la mobilité ; tous ces facteurs concourent à rendre de plus en plus souhaitable le recours aux interprètes pratiquant l’aller-retour, soit la biactivité.

Il y a tout lieu de croire que le deuxième secteur s’étendra à l’avenir aux dépens du premier. Cette tendance est marquée au sein du marché privé/industriel; à Paris, Bruxelles et Genève, et même au Pays Bas pour ne citer que quelques exemples, la demande reste très importante pour des interprètes compétents (et ce mot a de l’importance !) offrant la combinaison français-anglais en biactif.

Dans les pays européens, ainsi que ceux de l’Afrique sub-saharienne ou au Canada (pour ne citer que quelques exemples), les entités étatiques telles que les Ministères cherchent également activement de bons interprètes de conférence offrant en langue active la langue du pays et, notamment, l’anglais.

– Donc, pour l’interprète qui possède deux langues à un très bon niveau (voir dessus), l’option biactive est attractive et prometteuse. Cet(te) interprète possède peut-être d’autres langues de manière passive, et rien n’empêche de conjuguer les deux modes, afin de se rendre attrayant et utile à un maximum de clients et de configurations de réunions. Par contre, pour celle ou celui qui ne peut offrir qu’une langue active ‘classique’ et deux ou même trois langues passives qui le sont tout autant, il y a peu de débouchés qui permettent de vivre uniquement de l’interprétation de conférence. Demeure l’option d’apprendre une autre langue ‘exotique’, mais comment savoir lesquelles sont et resteront porteuses, et comment trouver le temps de les maîtriser à un niveau convaincant, tout en gagnant sa vie ?

En conclusion, au sein de la tourmente des évolutions commerciales et politiques de ce monde, et malgré les fluctuations que vit de notre profession d’interprète de conférence, l’interprétation biactive de grande qualité (impliquant donc deux langues dont la qualité active est au-dessus de tout soupçon) devient de plus en plus une valeur sûre qui permet à ses pratiquants de vivre de leur art. Par contre, les pressions budgétaires étant ce qu’elles sont et les écoles d’interprètes continuant à fournir une relève qui fait plus que compenser, numériquement, les départs de la profession, la qualité est une condition sine qua non. Voilà pourquoi il est plus que souhaitable de se doter, en toute connaissance de cause et après mûre réflexion, d’une langue ‘B’ à toute épreuve, et qui force le respect des clients ainsi que des collègues.

Avant de passer à la section suivante, je pensais qu’il serait amusant et instructif d’illustrer mes arguments avec un petit échantillonnage aléatoire (et nullement scientifique, s’entend) de l’annuaire de l’AIIC, en ce qui concerne le pourcentage d’interprètes ayant une langue ‘B’.

Le taux global de langue ‘B’, sur un échantillon total de 360 interprètes AIIC, est de 57%.

Voici la ventilation par ville ou par pays : Bruxelles 36%, Genève 50%, Etats-Unis 60%, Royaume-Uni 62%, Autriche 65%, Canada 72%, Paris 82%

Quelles peuvent être les conditions de base pour entamer cet apprentissage de manière réaliste ?

– la langue ‘A’ est au-dessus de tout soupçon

– la première langue passive, que l’on veut transformer en langue ‘B’, Est déjà très bien maîtrisée

– l’accent étranger, dans cette langue, est faible ou inexistant

– l’interprète en question a vécu ou est prêt à vivre au moins une année dans un pays où cette langue est parlée comme première langue

– l’interprète est prêt à travailler de manière assidue, en cabine et en en-dehors, pour établir les automatismes neuronaux et linguistiques requis par sa nouvelle combinaison. Il s’agit de refaire en partie l’apprentissage de l’interprétation sans doute déjà accompli, ce qui requiert bien entendu des dizaines d’heures passées en cabine à rôder cette seule combinaison

Quelles ont les démarches à assurer et les pièges à éviter, une fois la décision prise d’opter pour le rajout d’une deuxième langue active ?

Il s’agit de renforcer cette langue, et le bagage socio-culturel qui va avec, jusqu’au niveau où un délégué de cette expression s’y retrouve dans votre production linguistique, et se sent en présence d’un interlocuteur qui le comprend à tous les niveaux, qui partage avec lui/elle le sens d’un milieu de vie et de société.

a) Voici quelques exercices à privilégier :

1)

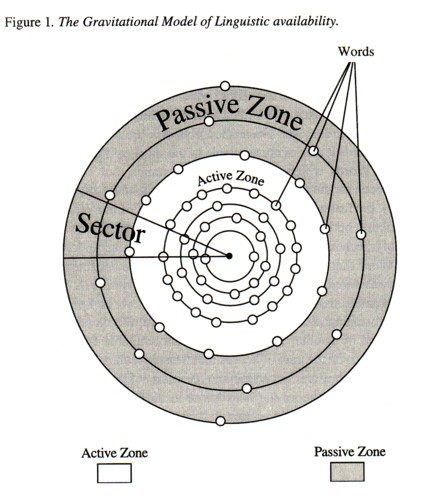

Passer beaucoup d’heures, en cabine, à prendre en filature (‘shadowing’) un intervenant parlant bien la langue ciblée. Il s’agit d’employer des fichiers MP3, des cassettes, des CD où l’orateur s’exprime dans les cadences de sa langue maternelle, et la maîtrise bien entendu à un très bon niveau. En filature, vous répétez le discours de l’orateur sans en changer la langue. Ainsi, votre cerveau et votre bouche doivent apprendre inconsciemment à intégrer et à produire cette langue sans effort mental, et réflexivement, ce qui exige évidemment des dizaines d’heures d’entraînement.

En agissant de la sorte, l’appareil neuro-linguistique assure environ 80% des opérations impliquées dans l’interprétation simultanée (une synthèse de plusieurs études récentes menées par des chercheurs spécialisés), le seul élément manquant étant le transfert linguistique. Il s’agit donc d’un très bon exercice à plusieurs niveaux.

Pendant la prise en filature, vous pouvez travailler la longueur du recul et la faire varier, et insérer petit à petit des expressions de votre propre facture. Il convient avant tout d’assimiler en automatisme les cadences et le relief vocal de la langue ‘B’ ciblée.

Le but ici est de constituer dans votre cerveau de nouvelles trajectoires nueronales ; ceci est un apprentissage indispensable pour toute nouvelle combinaison linguistique. Le fait d’avoir maîtrisé la pratique de l’interprétation simultanée entre une première et une deuxième langue ne dispense aucunement de travailler longuement, à titre séparé, chaque nouvelle combinaison – le cerveau devra se modifier en fonction, ce qui n’est pas le travail d’un jour.

A cette fin, il est également important de s’entraîner, pendant le travail de filature, à occuper une autre partie du cerveau, en écrivant par exemple (tout en parlant) des séquences de numéros qui exigent de la réflexion : 3, 7, 11, 15, 19….. Employer des séquences de plus en plus complexes au fur et mesure de l’apprentissage.

En travaillant en filature, il est tout-à-fait possible de réduire un accent étranger éventuel de manière considérable.

2)

En matière d’accent, la filature peut faire beaucoup, bien qu’au moins un reliquat subsistera presque toujours, et n’est pas une contre-indication en soi (voir dessus). Il existe dans toutes les langues une poignée de sons (qui variera en fonction de la langue et du pays de l’apprenti-interprète) que l’étranger aura des difficultés à produire : en anglais le ‘th’ ou le ‘..aw’ ou bien les accents toniques (se méfier notamment du mot ‘development’ !), en français les ‘..ouille’, ‘..u’ ‘en’, ‘in’, ‘an’ ou ‘on’, par exemple. Savoir quelles sont vos lacunes à ce niveau, et attelez-vous à apprendre à reproduire ces sons sans erreur, en vous exerçant jusqu’à ce que l’automaticité s’installe.

3)

Pour commencer à mesurer votre aptitude croissante dans la langue ‘B’, vous devrez guetter le moment où votre production de cette langue se fait automatiquement sans erreur grossière d’accent, de grammaire ni de syntaxe. Une fois acquis la certitude que, même sans surveillance ni censure mentale de votre part, la production de la langue ‘B’ se fait sans encombre, votre cerveau pourra commencer à passer au traitement intellectuel des sujets abordés et à la transposition de la langue ‘A’ ou ‘C’ vers la langue ‘B’ .

Une nuance ici : n’entamer l’apprentissage de la combinaison C > B qu’une fois acquis celui en A > B.

4)

La langue maternelle étant constituée en grande partie pendant la scolarisation secondaire, il est essentiel de refaire cet apprentissage, manquant chez ceux qui ne sont pas de parfaits bilingues, dans la langue ‘B’ visée. Il s’agit d’apprendre les notions et surtout les vocabulaires de bases manquants, en géographie, histoire, chimie, maths, physique, histoire de l’art, littérature etc. etc. Il peut être utile d’acheter pour ce faire les manuels scolaires de la langue en question, qui existent au bon niveau de connaissance et de langue, et qui auront été compulsés à l’époque par vos délégués e cette expression.

L’expérience montre que les deux domaines les plus souvent lacunaires dans la langue ‘B’ sont ceux des noms géographiques et de l’histoire de l’art et des cultures. Potassez tout de suite vos atlas, car ces vocabulaires ne pardonnent pas !

5)

Une fois les progrès de base accomplis, il est capital de rester au courant, en temps réel et en permanence, des évolutions culturelles/sportives/sociales du premier pays où la langue ‘B’ est parlée. Les films, la télévision, les journaux sportifs seront ici des atouts précieux.

6)

Passer du temps, régulièrement et pour des périodes aussi longues que possible, dans le(s) pays où votre langue ‘B’ se parle, en privilégiant les visites de musées et d’expositions, ainsi que des manifestations sportives et des cultures jeunes.

Il est parfois possible d’organiser une année de travail dans l’un de ces pays, en offrant vos services d’interprète qualifié comme lecteur ou assistant de cours à une école d’interprétation du pays. C’est le scénario le plus favorable, dans la mesure où vous restez dans le milieu de l’interprétation, dans la langue et la culture étrangères. En outre, il est parfois possible de prévoir un arrangement de troc où, en échange des cours que vous donnerez, vous pourrez assister à d’autres cours et vous servir des installations d’interprétation.

7)

Se munir d’un petit cahier où vous consignerez systématiquement toute belle citation, expression, image ou autre locution que vous rencontrerez, et que vous guetterez, dans la langue ‘B’ en devenir. L’idée ici est de rehausser le niveau global de votre expression, en étendue et en profondeur, en y incorporant des milliers de mots et de membres de phrase. Ces locutions, vous les apprendrez par cœur pour qu’elles deviennent seconde nature ; vous pourrez ainsi, petit à petit, rejeter en interprétation le premier mot qui vous viendra à l’esprit, pour privilégier systématiquement le deuxième ou le troisième, d’un registre meilleur.

8)

Choisir un beau discours dans la langue visée (et s’il s’agit de l’anglais, choisir entre celui du Royaume-Uni et celui des Etats-Unis, ensuite s’y tenir de manière cohérente) et s’évertuer à en apprendre une phrase par jour, en se la répétant de vive voix, le nombre de fois qu’il faut, jusqu’à ce qu’elle coule de source. Ne s’arrêter que lorsque le discours entier sera rentré dans votre mémoire et conscience. De cette manière, vous commencerez à maîtriser la grammaire, les cadences, la syntaxe, enfin le génie de la langue.

b) Il existe des pièges à éviter lors de l’emploi d’une langue ‘B’, et qui guettent tout jeune interprète :

– faire très attention en matière de registre, car celui-ci ne peut être jaugé avec la finesse habituelle dans la deuxième langue active. Toujours opter pour une locution ou une expression légèrement moins familière, ou moins musclée, que l’original.

– privilégier des phrases et expressions simples, sans céder à la tentation de clairsemer son discours en langue ‘B’ de locutions complexes, vieillottes, familières ou autrement hors du commun. Dans tous ces cas, et notamment avec l’emploi de métaphores ou d’images, il est très rare de pouvoir manipuler la langue non-maternelle avec une précision suffisamment certaine. N’imaginez surtout pas que l’une ou l’autre phrase prétentieuse, consciencieusement apprise par cœur, réussira à relever le niveau global de votre discours – au contraire, elles ne serviront qu’à perpétrer autant de ruptures de style, et attirer ainsi l’attention du client sur la relative pauvreté de la langue parlée par l’interprète

– la règle d’or est la suivante: « Keep it simple, stupid ! » Manier la deuxième langue avec sobriété, clairvoyance et intelligence, en respectant à tout moment ses propres limites. De cette manière vous viendrez gonfler les rangs des interprètes de conférence compétents et professionnels, vous serez respecté(e) et comblé(e) dans l’exercice de votre métier et vous apporterez votre pierre à l’édifice d’un monde où la communication est là au service de l’essor des hommes…

Chris Guichot de Fortis

(mars 2007, actualisé en 2011)