When you think of writing things down in simultaneous we usually think of writing down numbers or terms for our booth partner. But that is just one of the reasons to keep a pen and pad handy while working in simultaneous.

So what can we usefully note down when working in simultaneous?

1. Notes for your colleague

1.1 Numbers, dates, names

1.2 Terminology

Write them on a piece of paper in between the two of you, where the colleague can see it but is not disturbed by your writing it down.

– write big and clearly

– indicate (eg. with your finger) the note

– cross out each thing you’ve written down once it has gone by

Don’t

– Don’t distract the colleague to show them what you’ve written, they’re busy!

– use symbols or abbreviations (that aren’t absolutely obvious)

– write down anything that you’re not sure of (or get it wrong)

2. Notes for yourself

2.1 Numbers, dates 1

We often do numbers consecutively in simultaneous – we stop speaking, listen, write the number down and then read it out.

It’s a technique many use but that has its limits when there are lots of numbers.

2.2 Numbers, dates 2

It’s useful to keep numbers and dates visible on the page for future reference (later in the same speech or later in the same debate).

2.3 Names

– having a written version can help you work out what name really is (Egg not Hague)

– it’s quicker to read a name than to either reproduce it phonetically or try to “translate” the SL pronunciation of a name into TL pronunciation of the same name

– it’s useful to keep names visible on the page for future reference (later in the same speech or later in the same debate)

– also having a note means that you will pronounce the name consistently the next time it comes up

2.4 Long words

As with names it’s quicker and easier to read a long expression than to process it and/or fetch it from memory. So write them down and keep them visible.

eg. quantitative easing

For particularly difficult words you can even make the syllables or parts of the word clear to aid pronunciation

epi demi ological

ethylene propylene diene

2.5 Grammatical agreements

Some grammatical or lexical items require agreement later in the sentence. If so then it’s useful to note the determining item to remind you later what you need to base agreement on. This reduces cognitive load.

– if

It’s not a great idea to start a sentence with “if” but if you have to, then jot it down on the page so that when the second clause comes you can start with a clear “then”, making the structure clear to your listener (and even yourself).

– lists

Sometimes a list might start “we suggest: ”. In English each list item now has to be an (-ing) form eg. we suggest applying…. For lists it’s useful to note either the “suggest” or the “-ing” so you get all subsequent items correct.

eg. We suggest applying for residence permit at your local government office; making sure that all your employment papers are in good order and not dated more than 3 months previous to the application; and perhaps also consulting an immigration lawyer.

This is particularly useful when the grammar is different in the other language. In French for example you might use proposer as the translation of suggest. However proposerrequires de plus the infinitive

eg. nous proposons de faire or de and a noun as object nous proposons l’implementation de.

NB there is often a short pause before a list starts in English that will signal it to you. Alternatively as soon as you hear the second item in a list you write down your DETERMINING element, eg. – ING

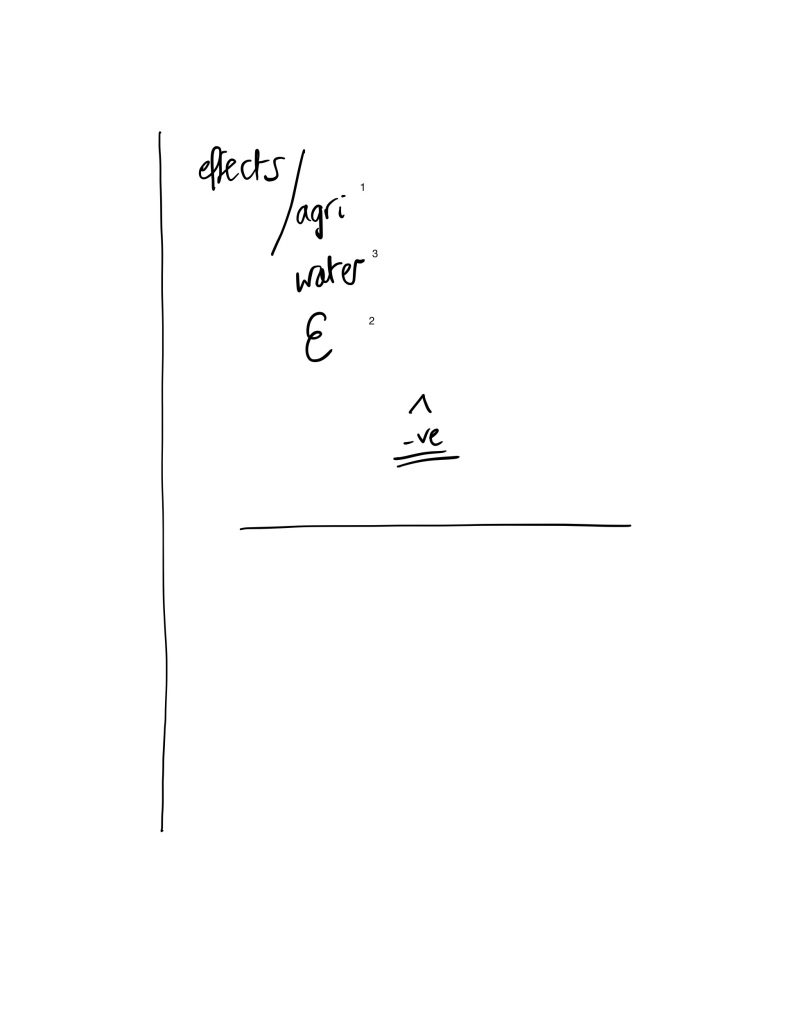

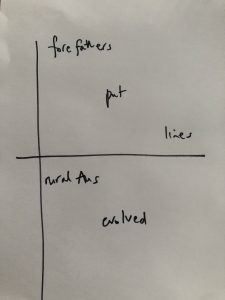

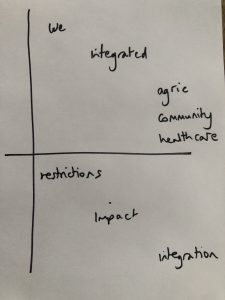

2.6 The structure of the speech

If the speaker announces that they will make a number of points, or enumerates longish points as they go along it’s helpful to take a short note of that to give you an overview of the speech you are interpreting.

eg.

1. EU

2. past

3. flows

Similarly digressions can be indicated by noting the item that immediately preceded the digresssion plus an indication of the digression (eg. brackets or NB)

immigration ( )

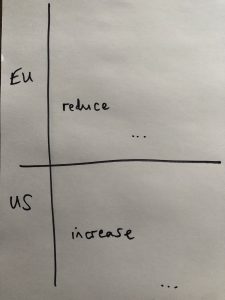

2.7 Context

Keeping a note of comparative information over the course of a speech, or who has said on the main issue over the course of a debate can be an extremely useful way of keeping an eye on the context in which each subsequent remark is made.

eg.

FR 112m euro

DE 300m euro

UK 75m euro

or

S & D against

EPP for but… amendment 6

ECR for

Greens against

Notes in Simultaneous, Andy Gillies 2020