The following is taken from Consecutive Interpreting by Andrew Gillies, Routledge, 2019 (p132-136), and suggests a way of breaking down (analysing) speeches you listen to.

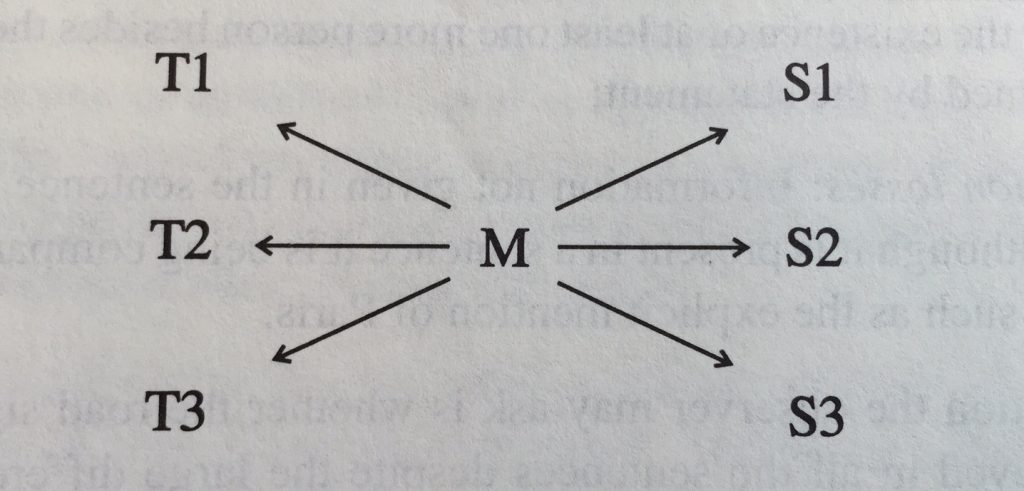

There are of course many ways to express any message in any language. As Rozan (2002: 16) also famously wrote “Take any French text and give it to 10 excellent English translators. The result will be ten very well translated texts, but ten very different texts in as far as the actual words used are concerned.”. That means that there are always several ways to reformulate any given chunk of source language successfully. This was nicely illustrated by Gile in an experiment on translation fidelity. Gile’s experiment starts with the information to be transmitted, the Message.

If the versions in L1 (Language 1) correctly transmit the message, M, from the roadsign, and likewise for the L2 (Language 2) versions, then in theory then any one of the sentences in L1 could be translated by any one of the L2 versions. In this way Gile demonstrates that the interpreter can both be faithful to the original AND reformulate in several different ways. Gile’s conclusion (1995:58) is a little more complex but this diagram is a very useful model for us in consecutive as we will see a little later when we attempt to show how the consecutive format helps us reformulate.

…

Why reformulate?

There are a number of reasons that you will want to reformulate when interpreting…

- the interpreter should produce a natural sounding (idiomatic) and articulate target language version of the source speech. This is easier on the listener’s ear and also improves the communicative effect of what the interpreter says.

- to achieve a version “with the same meaning and equivalent effect# as the source speech) then reformulation is essential. ” (Jones 2002:82). The hierarchy of points, the force of the presentation and the register of the language should all come across as the same regardless of whether the listener is using interpretation or listening to the original. For example you can sometimes translate the French word déontologie as deontology in English, however in most contexts the word would appear rather unusual to an English listener as it belongs to a different register of language. An English speaker would more likely have used the term ethics in the same situation, eg. professional ethics.

- a one-to-one translation of a given word may not exist (or may be stylistically incorrect – see previous point). Eg.précarisation in French which means (in some contexts) the erosion of job-security in the labour market but there is no single word for this in English.

Reformulation is also useful for you as a student of conference interpreting because it…

- hinders word for word translation and therefore promotes analysis of the speakers intended message and idiomatic production.

- teaches reformulation in a context that is less demanding on mental capacity that simultaneous. You’ll then be better prepared to reformulate in simultaneous.

(These lists are considerably inspired by (in chronological order) Weber 1989:32; Shlesinger 1994; and Jones, 2002:81-95.)

…

How does consecutive facilitate reformulation

Consecutive offers two enormous advantages over simultaneous when it comes to reformulation. Both the consecutive and simultaneous interpreters are trying to arrive at a natural target language version of the original speech’s message – which will inevitably require reformulation. The consecutive interpreter however, works in two phases. This means firstly that when they are speaking their version they no longer hear the original language in their ears (or echoic memory) as simultaneous do. That means that language interference is much less of a problem in consecutive. Also the consecutive interpreter has two steps in which to arrive at the natural sounding version where the simultaneous interpreter does not. This is something we can exploit to our (and our listener’s) advantage. As we know there is a listening Phase (1) and a Speaking Phase (2) for the interpreter. Whereas the simultaneous interpreter has to find a reformulated version almost instantaneously the consecutive interpreter has two attempts, or steps, to do the same. That doesn’t mean either that you have to arrive at a good version entirely in Phase 1 or entirely in Phase 2, although you may, but rather the real advantage of consecutive is that the interpreter can take two incremental steps to get to the target version, building on a partial reformulation made in Phase 1 when they get to Phase 2.